ABOUT THE GFRN | APPLICATION GUIDELINES | GFRN STORIES | GFRN FAQ

‘Better late than never’: Myanmar bans timber exports to save remaining forests

Morgan Erickson-Davis, mongabay.com

April 24, 2

Myanmar contains some of Asia’s largest forests, but has been losing them at a rapid pace during the last two decades as logging companies emptied woodlands to meet the demands of the lumber industry. In an effort to save its disappearing forests, Myanmar implemented a ban on log exports, effective March 31, 2014. However, the ban affects only raw timber exports, not milled lumber, throwing into doubt its ability to significantly curb deforestation.

Myanmar boasts a variety of environments – from the Himalayan foothills of the north, to the fertile plains surrounding the Irrawaddy River in its center, to the tropical forests and mangroves of its coastal south. These diverse habitats support a huge number of species, making it one of the most biodiverse places on the planet. Its residents include many endemic species, such as the white-browed nuthatch (Sitta victoriae), Myanmar snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus strykeri), Burmese star tortoise (Geochelone platynota), and Burmese roof turtle (Batagur trivittata). In total, 233 threatened species are found here, 65 of them classified as Endangered, and 37 as Critically Endangered by the IUCN.

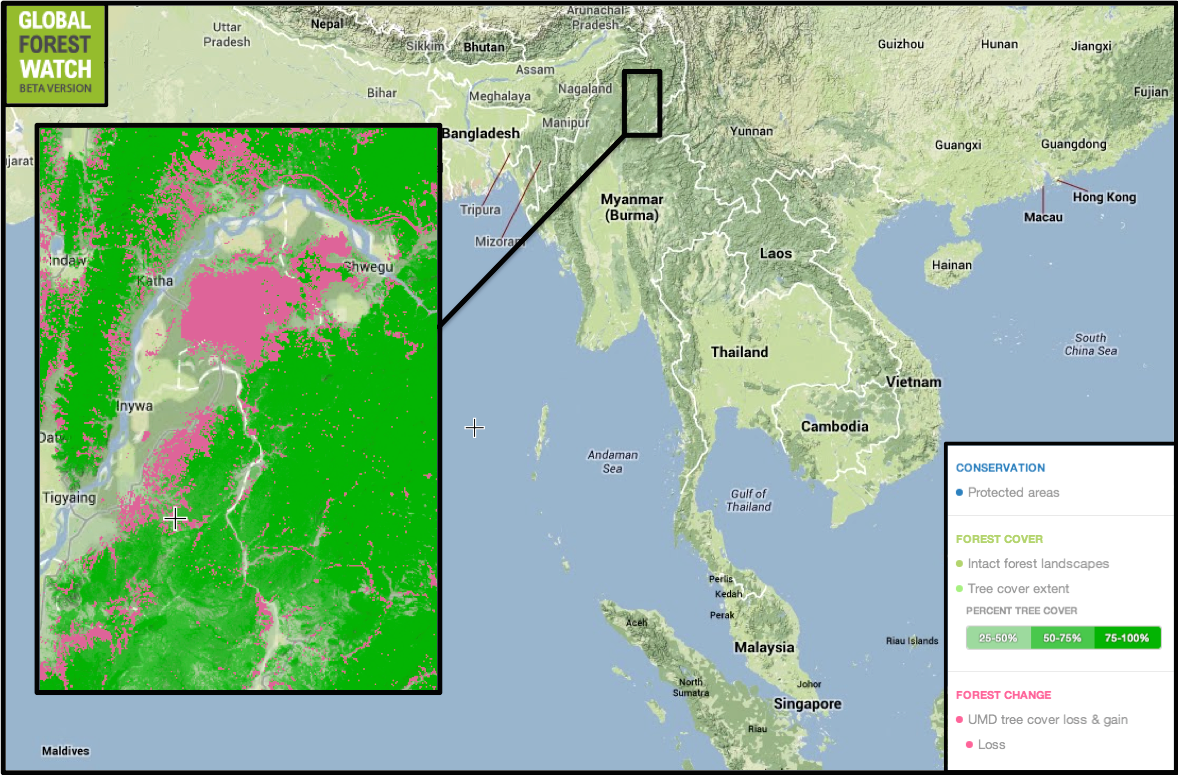

Deforestation has denuded the banks of the Irrawaddy River in the north of Myanmar, where some areas have lost more than half their forest cover. Courtesy of Global Forest Watch. Click to enlarge.

Habitat loss through deforestation is one of the primary drivers of population declines in Myanmar. According to Global Forest Watch, approximately 1.5 million hectares of forest were felled between 2000 and 2013, much of it harvested illegally. The damage is most concentrated along the northern reaches of the Irrawaddy River where, in places, more than 60 percent of the land has been logged over the past decade. Many of these areas show little to no forest grow-back, particularly along the river.

Without roots to bind the soil, riverbanks erode into the water, making rivers wider, shallower, warmer, and murkier. Warm water also holds less oxygen than cool water. Aquatic species that are adapted to clear, cold water may not be able to contend with these new conditions; for instance, silt can accumulate on the gills of fish, suffocating them. These effects echo through the food chain, impacting many species across many ecosystems.

The Irrawaddy dolphin (Orcaella brevirostris) is one such unfortunate bystander. Listed as Critically Endangered in Myanmar, scientists estimate only 58-72 exist in the Irrawaddy River. Scientists believe its decline is hinged on steep reductions in fish populations, caused, in part, by the impact of deforestation on water quality. Interviews with area locals indicate that the situation has worsened significantly in just the last two years. The reported average catch size by fishermen in 2012 was 25 kilograms (55 pounds); in 2014 catch-size had plummeted by more than 80 percent. In addition to fewer available fish for the dolphins, local fishermen have adopted new techniques to maximize catches. One of these, high-voltage electrical shocking, has been shown to kill dolphins that are swimming nearby.

There are only 58-72 Irrawaddy dolphins left in the Irrawaddy River. Their decline is due in part to habitat degradation from deforestation. Photo by Stefan Brending.

Myanmar enacted the timber export ban in response to ecological repercussions, together with the fact that trees were simply running out. Even industry officials supported the ban, as remaining resources dwindled to point at which Myanmar was left without sufficient raw lumber to manufacture finished products. Teak (Tectona grandis), is especially valued for furniture and boats because of its durability and water resistance. Prior to the export ban, Myanmar exported an estimated third of the teak lumber supply worldwide, and was the only country that still exported raw teak logs from natural forests rather than from plantations.

According to Global Forest Watch, of Myanmar’s total land area of 67.7 million hectares, only approximately 6.3 million hectares – less than 10 percent – consists of intact forest. Much of this exists in the country’s mountainous north, where forests are less accessible to logging outfits. In contrast, there are no intact forests in the entirety of Myanmar’s eastern portion. This region of approximately 12 million hectares also contains no substantial protected areas – despite its status as a biodiversity hotspot.

No intact forest exists in the entire eastern portion of Myanmar, and only one small area is protected. Courtesy of Global Forest Watch. Click to enlarge.

In addition to the export ban, Myanmar is also planning to reduce domestic-use harvest quotas for teak by 80 percent in 2015. However, as much of the country’s logging is done illegally, it remains to be seen how effective a new quota will be.

There are doubts as to how successful the ban will actually be when it comes to preserving Myanmar’s forests. While it effectively ends the export of whole logs, it does not affect milled timber. In response, many lumber yards are being set up throughout the country. One of these, established in Yangon by the Singapore-based Concorde Industries, plans on milling 10,000 tons of wood annually for export to Europe. Critics also cite a lack of clarity from the government regarding implementation of the ban and illegal harvests.

“Now there’s a strong push in the [Myanmar Timber Merchants Association] and the [Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry] to clamp down on illegal logging, but it’s not clear to me what illegal logging in this context actually means,” Kevin Woods, a researcher with the NGO Forest Trends, told Myanmar Times.

“Does that mean that logging is being done by villagers and then sold to businessmen without the explicit permission of [the ministry]? Or could it also mean, as I feel it should … logging being done by crony companies in natural, unmanaged forests? None of that is clear to me from any statement made by any government officials.”

The rush to fill cargo vessels with timber before the ban became effective resulted in frenzies at wharves along Myanmar’s coast. Many exporters believed that either the ban would be rescinded or the deadline extended, and so had not made advance plans to ship their stores. Because of this, the total March export that was three times larger than the average monthly export in 2012, and an estimated 90,000 cubic meters (3.18 million cubic feet) of surplus timber remains unshipped.

The export ban had been in the works since the 1990s, but it took 20 years and the loss of millions of hectares of forest to make it a reality.

“Of course, this ban should have been imposed a long time ago, “a forestry ministry official told Reuters, “but it’s better late than never.”

A riverside village in Myanmar. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

After widespread deforestation, China bans commercial logging in northern forests

Morgan Erickson-Davis, mongabay.com

April 22, 2014

Forestry authorities in China have stopped commercial logging in the nation’s largest forest area, marking an end to more than a half-century of intensive deforestation that removed an estimated 600 million cubic meters (21 billion cubic feet) of timber. The logging shutdown was enacted in large part to protect soil and water quality of greater China, which are significantly affected by forest loss in the mountainous region.

The area is in the extreme northeast portion of China, and comprises a huge swath of dense, temperate forest that stretches into Russia. The landscape is dominated by the Hinggan (Khingan) mountain range that spans more than 1,200 kilometers (750 miles) south towards China’s interior, and supports a diverse array of wildlife. The Hinggan Mountains also form an important climatic divide, taking precipitation from southeasterly winds and fueling watersheds that provide water to a tenth of China’s arable land.

Widespread deforestation in the Hinggan region from 2000-2013, represented in pink. The only intact forest is a small region indicated by light green in the upper left corner. Courtesy of Global Forest Watch. Click to enlarge.

Large-scale commercial logging of the area first began in the 1950s to meet growing economic demands. By the 1980s, the landscape of the region had changed dramatically due to the loss of forest cover, and large trees had all but disappeared. From 2000 to 2013 alone, more than half a million hectares of land were deforested in the region, according to data from Global Forest Watch. Logging activity was focused primarily in the northern periphery of the range, where around 20 percent of the land was deforested

Forests are vital to maintaining healthy watersheds. They help to catch water from the air, and they even provide it via their respiration processes. Additionally, their roots help to hold water in the soil. Without trees, droughts become more commonplace. When rain does fall on a deforested area, it isn’t released into streams gradually, but instead is discharged as a deluge, overwhelming streams and rivers. Without tree roots to bind them, riverbanks erode, sullying water and completely changing stream ecosystems. Downstream habitats that evolved to rely on a constant supply of water are often damaged by the feast-or-famine conditions brought about by deforestation.

The impacts of logging in the Hinggan range have been becoming increasingly evident, sparking major environmental problems.

“There are no longer any big trees. The winds in the Greater Hinggan Mountains are becoming stronger and the woods can no longer retain water,” Liu Zhanhun, a worker with the Qianshao Forestry Station, told Sina News.

“In the past, it rained for days before water levels in rivers could rise. Now the river water levels can rise substantially following just one rainstorm,” Liu said.

The Yalu River in the Greater Hinggan mountain range. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0.

In addition to droughts and floods, the total area of wetlands in the region has shrunk to half its original size, and forest fires have become more prevalent. In 1987, a fire of unprecedented size burned 10,000 square kilometers (3,900 square miles) of forest.

The rapid forest loss in Hinggan runs counter to the official narrative that China has eliminated deforestation through law enforcement measures and reforestation programs. According to Global Forest Watch, China lost some 6.1 million hectares of forest cover between 2000 and 2013, only 2.2 million hectares of which was offset by the establishment of new forests. Forest loss during this period was particularly concentrated in the southeastern part of the country, with a total loss of more than four million hectares.

In reaction to the growing crisis in the Hinggan range, China’s government began enacting protections of the area more than a decade ago while still allowing commercial logging. However, a forestry development plan warned that if logging were not stopped completely, the Hinggan forests could entirely disappear.

Yet, while many people are in favor of the ban, there are others whose livelihoods depend on the logging industry. A third of all Hinggan timber workers make only subsistence wages, and use wood to heat their houses during the frigid winters because they can’t afford to buy coal. In light of this, China’s government has earmarked $378.6 million (2.35 billion yuan) of annual aid for the workers, which will continue until 2020. Many communities are also considering the development of tourism industries for employment options.